Last month we talked about crew: finding them, convincing them to sail with you and then integrating them into your unique shipboard living situation. It’s a skipper's best kept secret that the tables turn once you are at sea. When still ashore, it is often the crew that is working to gain the skipper’s confidence. Now that you’ve moved onto the sea, it is the skipper that is working to keep your buoyant utopia running smoothly. Once you are out of sight of land, a clever skipper will focus on keeping the boat’s crew content if not cheery.

If you and your new crew are pairing up for a long journey, don't rush straight out to sea. The first part of your voyage should be leisurely. Start with a couple of coastal hops. Your crew may need time to adjust to the boat and life at sea and you should take some time to get to know them. In the rare case that you find that you are somehow incompatible, you still have the option of pulling in somewheres to lose a few pounds.

My first paid crew position was on a yacht sailing across the Pacific. The boat had a very accomplished, though young, skipper. I learned a lot on that boat. One thing that the skipper was not good at was priming the crew when approaching the dock. No matter how well my fellow crew and I would second-guess the situation, we would eventually get it wrong ... and name calling would ensue. When I found myself in the position of skipper (on my next yacht job), I had decided to handle things a little bit differently. When coming in to dock, when anchoring, when jibing or when doing any activity-intensive boat manipulation, I would have a little crew pow-wow. We would get together and I would go over how I envisioned the episode playing out along with a possible backup scenario, finishing up the meeting with the statement, "It may not go like that at all but I'll make sure you know what I'm thinking." It was how I wanted to be treated as crew.

Last month I mentioned the two things I look for in crew. I look for crew that gets along with everyone and crew that is not overly prone to getting seasick. I believe that seasickness can be caused by nervousness or fear. As skipper, it’s my job to make you feel safe. Your overall experience should involve a general sense of safety and wellbeing. This starts with your introduction to my vessel. I show crew around pointing out the location of both fun stuff and safety stuff with some procedure mixed in. I used to not sleep well when I first joined a boat. I would worry about the overall integrity of a vessel until after that first rough water experience aboard. Once I saw that the boat could withstand a little weather I would sleep like a baby. During my crew-to-boat introduction, I like to weave into the conversation a little story about the boat taking some bad weather in stride to indicate how sturdy she is.

The way the skipper handles problems can go a long way in keeping shipboard tension to a minimum. Instead of getting upset or excited when the unexpected occurs, I approach problems as a challenge or as a game that we can all band together to win. It is always good to keep everyone onboard involved in the boat’s progress toward its destination.

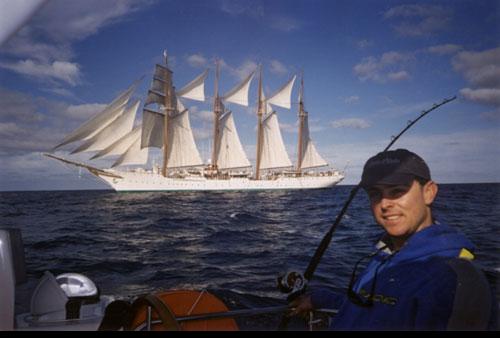

A good at-sea distraction for the crew is the points game. This game also helps to keep watches more fun and more effective. A point is awarded every time a ship is spotted, two points if you are off watch and the person on watch has not seen it. Pods of whales, sharks, turtles and other unusual marine life are each worth a point. No, no points for dolphins since you see them all the time. We award two points for the person who guesses closest to the time we’ll reach the half way point in miles. Another two points go to the crewmember that is closest to the arrival time at the destination. A point is awarded each day for the one who guesses closest to how many miles had been traveled in the last 24 hours. Did I mention water spout points?

Space onboard cruising boats can be scarce. One thing that can keep closely confined crew from going a little crazy is to provide them with a comfort zone. They need to have an area onboard that is their own. Sometimes, the only space a crewperson will have is their bunk. But it is theirs and it is not to be disturbed by anyone else aboard. Need to get some parts from under your crew's bunk? You ask them.

Your crew may not always be completely blissful but they should be as comfortable as possible. Inexperienced crew will come aboard without foulies. You will need to provide them. Even in the tropics, staying dry is paramount to comfort. Salt, my personal archnemesis, requires battling on all fronts. On boats where the helm is somewhat or totally exposed, the crew should be able to come in from watch, strip down to their fuzzy layers and be totally dry. I used to love that: battling it out with the elements for a few hours at the helm, pounding the boat into big seas, watching the tops of waves breaking off at the bow and come crashing back to wash over me in the cockpit. I would hand over my watch, remove my foulies, rinse the salt from my face, hands and feet and climb warm and dry into a cozy bunk, a tempest still raging outside.

I always give the watch person the best seat in the house. You want them to be comfortable and still have good visibility. I had a problem on Low Key. The best seat was on the high side of the cockpit, tucked under the dodger, in the big beanbag. It was comfy. The problem was that my crew would fall asleep. That setup may have been too comfortable. I’ll never forget the story Bob told me about his sleepy crew. After waking and warning the guy on two separate occasions, Bob found him asleep a third time. Bob unloaded a large handgun into the sea just a foot or two from the crewman’s head. The guy didn’t sleep on watch after that. Of course, he don't hear so well no more neither.

In the end, the way you treat your crew can make all the difference in how much they enjoy their voyage with you and your boat. And for you, happy crew means happy days at sea.

www.captainwoody.com

No comments:

Post a Comment